Evolution of oil sands mining

| Initial efforts to commercialize the oil sands were not focused on energy production, but on other uses for the oil from the oil sands.

In 1927, entrepreneur R.C. Fitzsimmons used Karl Clark’s process to separate and produce bitumen to be used as a component in roofing and road surfacing. The Alberta government took over the plant in 1948 in order to investigate extraction methods with large-scale equipment. By 1949, the plant was processing 450 tonnes of oil sands a day. Data from the experiments was used as the basis for a major study released in the 1950s by the Government of Alberta that confirmed the viability of profitable commercial production. |

|

| It wasn’t until 1963, after the Government of Alberta created an oil sands policy to supplement existing conventional crude policy, that the first major private investment in an oil sands project was made. Sun Oil (now Suncor) committed almost $250 million in the very first oil sands project, also known as the Great Canadian Oil Sands (GCOS) Project. Construction on the Fort McMurray facility began in 1964 and in 1967, the Suncor project became the world’s first oil sands operation.

In 1964, the Syncrude consortium was formed to do research on the economic and technical feasibility of mining oil from the Athabasca oil sands. In 1973, construction began and the first barrel was shipped on July 30, 1978. |

|

| Syncrude and Suncor continued to make steady progress improving oil sands technologies and an entirely new extraction process called Low Energy Extraction was developed and proven, bringing decreased costs and increased environmental benefits. | |

| In 1996, a federal-provincial agreement on oil sands royalties made the Alberta oil sands an attractive investment. This combination of technology improvements and the implementation of appropriate fiscal terms for the oil sands kick started a development wave and in 1999, Shell Canada announced a joint venture with Western Oil Sands Inc. and Chevron Canada Limited to develop the proposed Athabasca Oil Sands Project. In early 2009, CNRL’s Horizon Oil Sands Project successfully produced its first barrels of crude.

Today, technology continues to improve, environmental impacts are being addressed, and operating costs are being reduced, encouraging even further development. After 40 years of hard work, as conventional crude reserves decline, Alberta has become the most important source of new oil in the world. |

|

| To discover what mining projects are currently underway, visit the OSDG project status.

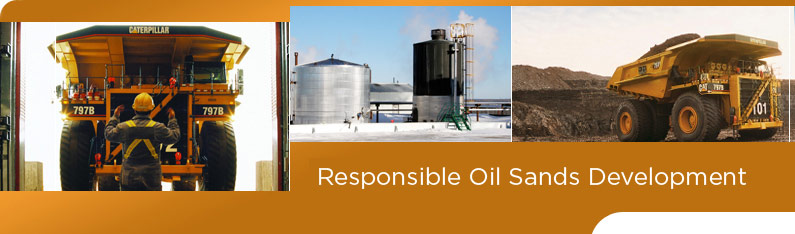

Oil sands technology - continuous evolution Early oil sands mining technology, such as that used in Suncor’s GCOS Project, involved giant excavators called bucket wheels that used toothed buckets mounted on the rim of a revolving wheel to both remove the overburden and then scoop up the sand and place it on a conveyor belt. When Syncrude Canada Ltd. opened in 1978 they introduced gigantic draglines which were perched on top of the ore body following the removal of the overburden. The draglines utilized a heavy toothed bucket attached to a cable from the end of a boom into the oil sand. The bucket was dropped down over the edge of a mine face and dragged back up the oil sand face to scoop up the sand and then place it in a windrow on top of the ore body. Bucket wheels were then used to reclaim the oil sand ore from these windrows and place it onto the conveyors. The oil sand was transported via conveyor belt to the processing plant where water was added to the oil sands, creating slurry that was conditioned using large tumbler drums. Truck and shovel mining today Today, draglines and bucket wheels have been replaced by giant, more cost-effective trucks and hydraulic shovels. Use of these shovels allows the operator to be more selective than the operators of the large draglines and bucket wheel could be in loading the oil sands, which vary in both depth and quality. As technology evolves, trucks and shovels continue to grow in size. The increase in equipment size improves both operating costs and reduces emissions intensity (a measure of GHG emissions per barrel of oil produced). Today’s trucks carry more than 400 tonnes at a time while the shovels can load an average of 100 tonnes per swing. |

|

| O & K Bucketwheel (Syncrude Canada) | Draglines and bucket wheels have been replaced by giant, more cost-effective trucks and hydraulic shovels (Syncrude Canada) | Mining trucks have progressively grown in size (Syncrude Canada) |